Back to the news list

Back to the news list

At a time when the second wave of coronavirus is decimating the world economy, when the Caucasus is smouldering from the consequences of the Karabakh issue and all the protracted Middle Eastern conflicts are continuing to drag the region into political obsolescence, the last thing we needed was a flareup with regard to the South China Sea. Territorial disputes in China’s maritime underbelly are by no means a novelty – just think of the Paracel and Spratly Islands or the Scarborough shoal, China has managed to have simultaneous arguments with Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines. Now, however, the initiative is coming from the Philippines, desperate to kickstart their gas production.

The President of the Philippines Rodrigo Duterte has lifted a 6-year moratorium on upstream drilling in a part of the South China Sea that is also claimed by China. The moratorium was initially levied by then-President Benigno Aquino as a precautionary measure amidst the Hague Arbitration which eventually invalidated China’s almost all-encompassing claim to the South China Sea. For obvious reasons Beijing refuses to accept the 2016 Hague Arbitration ruling, however the court judgment means that hypothetically all the subsea hydrocarbon reserves that are to be found within the 200-mile exclusive economic zone of the Philippines should be developed under the aegis of Manila. This should also include the Reed Bank (called Recto Bank in Philippine lingo), one of the most promising offshore prospects of the region.

It only took a couple of days to placate regional fears of territorial feuds moving back into hot phase – the Chinese Foreign Ministry announced that Beijing and Manila have agreed on the joint exploration of the South China Sea. Seemingly the covenant was struck several days before that when the Philippine’s foreign minister Teodoro Locsin travelled to China. Although both sides have so far been rather tight-lipped on the extent of the cooperation, it might be deduced that the joint venture will cover exploration and potential production within the area that the Hague Permanent Court of Arbitration has already presented its adjudication on. Given that China has refused to acknowledge the legal authority of the PCA to rule on the issue, any unilateral move by the Philippines would have been counterproductive and be met with Chinese naval harassment.

Hence, a joint venture with China is a temporary win-win for both sides: China gets partial access to territories which legally go beyond its territorial and maritime borders, whilst the Philippines can untap a heretofore unused territory and thus stop its declining rates of gas production. Politically the decision is much harder for the President Duterte of the Philippines – selling the idea of increasing Chinese naval presence in territorial waters that an international arbitration has ruled to be his own might be a difficult call to present domestically, especially Duterte’s pugnacious ruling style. This might explain why Chinese communiqués have been much more upbeat than Philippino ones, the latter still not reporting on any official deal concluded (so the risk of no-deal remains firmly on the table)

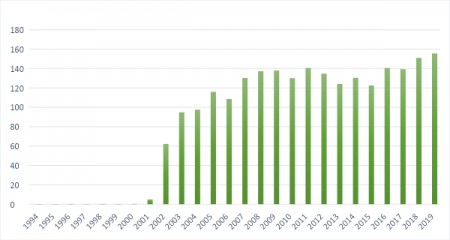

For the Philippines, finding new viable ways of supplying natural gas to the mainland is one of the crucial challenges of the nation’s energy policy. Currently most of its gas output comes from the Malampaya field, located in water depths of some 3000 meters to the west of Luzon Island, the total proven gas reserves of which stood at 2.7 TCf. Considering that Malampaya has been producing since 2002, it should come as no surprise that the field is assumed to start its production decline starting from 2022. It is against this that Chevron has sold its 45-percent concession rights to the local firm Udenna in late 2019 (the late was finalized by this March). Moreover, with the concession running out in 2022, the project’s operator Shell has reportedly been interested in selling its 45-percent stake, too, a move which is certain to bleed white Malampaya.

Graph 1. Annual gas production in the Philippines 1994-2019 (in billion standard cubic feet).

The same 2022-2023 deadline also applies for most of natural gas supply contracts vis-à-vis end consumers in the Philippines, 5 power plants operating in Luzon. Hence, spinning a new positive story around the Philippines’ offshore areas that had not been assessed yet is a much-required prerequisite to kickstart new production. As it happens, Manila is on the verge of becoming an LNG importer due to the shortage of domestically sourced energy, prompting the regional authorities to consider 4 LNG terminal projects that could bring in the missing 4-5 mtpa LNG of natural gas. The first of such projects has already received the green light from the Filipino government – a 5mtpa capacity LNG terminal will be built by a joint venture of First Gen Corp. and Tokyo Gas nearby Batangas City, located on the Southern Luzon Island.

Hence, the Philippines face declining domestic production amid ever-increasing demand, all this aggravated by the prospect of LNG imports, the first of which is assumed to arrive at some point in the summer of 2022. It is against this background that President Duterte’s decision to lift the offshore drilling moratorium ought to be assessed. The main question that remains to be answered is whether Manila will want to have a go at drilling in the South China Sea all by itself or it would prefer to involve China. The latter is certainly a lot safer, taking the edge off a long-standing territorial dispute and ensuring a level of political backing that the Philippines all by themselves could not garner, however might feel very much unearned and coerced. The choice is there.

Không thể sao chép