Back to the news list

Back to the news list

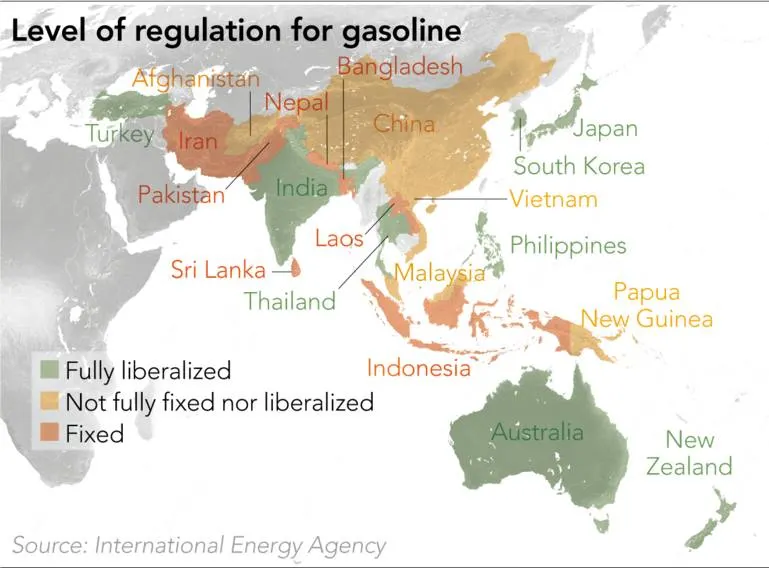

An oil price surge is pressuring Asian governments to control the price of gasoline, and while some have allowed prices at the pump to rise, others are eating the costs for fear of stoking public anger.

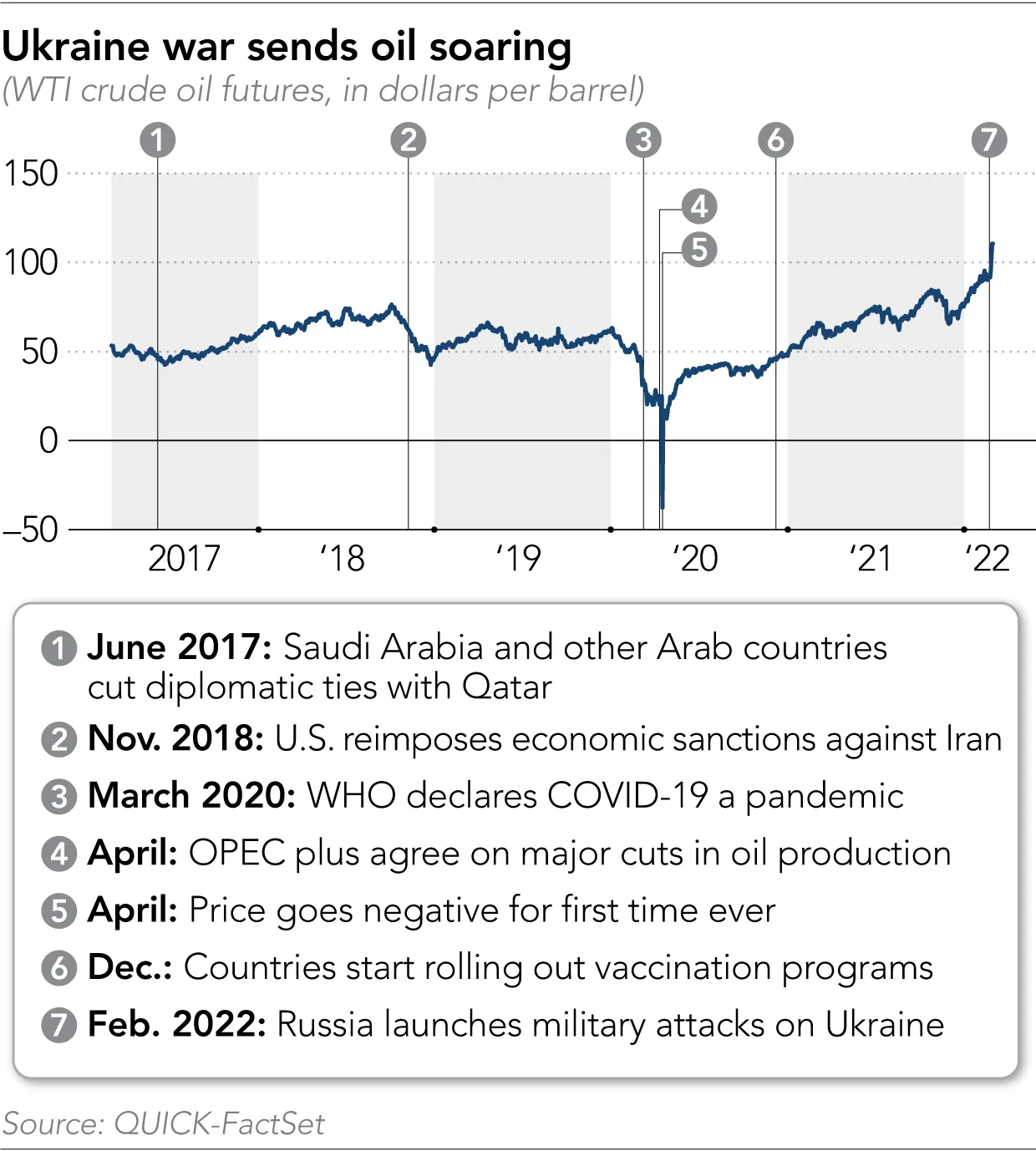

With the war in Ukraine sending West Texas Intermediate crude as high as $130 a barrel on Monday, Mar. 7, for the first time since 2008, the Vietnamese and Japanese and other governments are implementing or considering measures to ease consumers’ economic burdens.

But governments in Turkey and elsewhere are not, as the cost of regulating fuel prices grows too high. “Sorry,” read a sign at a shuttered gas station in Vietnam last month, “prices are being changed.”

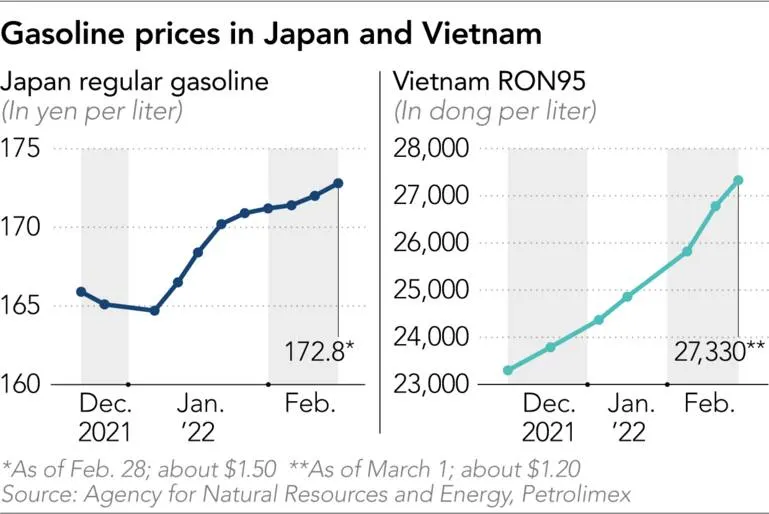

In the communist country, where gasoline prices are set by the government, the cost of a liter of 95 octane fuel has been raised six times since Dec. 10, increasing 17% in three months. Consumers’ pain has been compounded by a supply shortage. Motorbike riders trying to fill up at hundreds of gas stations last month found pumps put away and signs telling them to return later.

This led to speculation that gas station operators were stockpiling until the next price hike, which can only take place on certain days of the month. Drivers want the state to prevent such manipulation.

“People will be very concerned” because the costs hit their pocketbooks and “many other aspects of life,” Tong Quoc Su, a 32-year-old product designer, told Nikkei Asia. The state should stop companies from “hoarding, waiting for high prices.”

The Vietnamese government has pulled what levers it can. The trade ministry, which sets prices, plans to auction off reserves, the government’s Voice of Vietnam reported, and has ordered an increase in oil imports, which were triple the monthly average in February.

The shortfall at least partially stemmed from financial issues that threatened to idle the country’s biggest refiner. In January, the Nghi Son Refinery reduced capacity to 80% and suspended some crude imports because it lacked “enough liquidity to purchase new cargoes,” according to S&P Global Platts. The commodities data provider attributed the cash crunch to Vietnam’s pandemic-induced downturn in 2021.

While Vietnam’s parliament is discussing fuel tax cuts and other ways to reduce prices, inspectors have launched a nationwide investigation into the hoarding allegations. At least eight gas station operators have been fined or had their permits revoked for closing without permission, according to a message the trade ministry posted Feb. 22 on its website.

With disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia dominating oil markets, the costs are mounting for other governments that regulate fuel prices. In Malaysia, economists estimate fuel subsidies will cost the government between 12 billion ringgit ($2.8 billion) and 15 billion ringgit this year.

This is despite the government trying to move away from subsidies in recent years. Diesel and 95 octane petrol remain under government control, with the price of diesel capped at 2.15 ringgit and that of the widely used gasoline at 2.05 ringgit per liter. The removal of subsidies remains politically sensitive as such a move would affect the federal government’s reputation among the working class.

In Indonesia, the government is maintaining current prices for most grades of gasoline sold in the country with subsidies. State oil company Pertamina dominates retail sales of gasoline nationwide, and over 80% of its gasoline sales by volume are of subsidized regular-grade Premium and medium-grade Pertalite, prices for which have not changed during the pandemic.

The country’s energy ministry on Feb. 27 admitted subsidy spending will swell beyond what has been budgeted. The government allocated 77.5 trillion rupiah ($5.3 billion) for direct fuel and liquefied petroleum subsidies this year, based on an assumed crude oil price of $63 per barrel. For every $1 per barrel increase, the government must add an estimated 2.65 trillion rupiah in fuel subsidies for vehicles alone.

In the past, attempts to cut subsidies and raise retail gasoline prices have led to wide, often violent, protests in Indonesia’s major cities.

Sung Eun Jung, a Singapore-based senior economist at Oxford Economics, said subsidizing fuel will keep Indonesia’s inflation level under control but “will weigh on fiscal balance.” She forecasts a small improvement in Indonesia’s fiscal deficit this year, to 4.4% of GDP from 4.6% in 2021. “If the uptrend continues beyond [the first half of 2022], we could see more measures to pass the costs on to the public,” Sung predicted.

In Japan, the government in February said it was increasing the maximum level of subsidies for oil distributors to 25 yen (22 cents) per liter of gasoline, up from 5 yen, to prevent a sudden rise of retail prices. The government was also considering whether to instead reduce the fuel tax by 25.1 yen per liter. This option, however, invited concerns as already strapped municipal governments currently receive a portion of the fuel tax revenue.

In India, state-owned fuel retailers have been freezing rates during state elections, according to local media reports. Many predict prices will rise once the elections end this week. In Cambodia, where prices at the pump are up 17% since December, officials said the government could not further subsidize fuel due to budgetary constraints. It currently provides subsidies of about 4 cents per liter.

And in Turkey, a collapse in the currency has made the increase in the price of oil doubly painful. The government since 2019 has operated a sliding scale of fuel tax reductions to keep prices under a ceiling. The system last year resulted in around 60 billion lira ($4.2 billion) of lost tax income. With the oil price climbing even higher, it was abandoned at the beginning of March.

“If [the government] had done more,” said Ozan Bingol, author of several books on Turkish tax policy, “then they could not support other utility prices like electricity, [which] are also subsidized.”

In Istanbul, gasoline is now priced at 18.7 lira per liter, up from 9.67 lira in early December. The steep rise has contributed to a surge in inflation, which hit 54% last month. But locals have noticed a silver lining: With fewer people who can afford to drive, the city’s chronic traffic congestion has eased.

Không thể sao chép