Back to the news list

Back to the news list

Times of recession usually bring up overused terms like belt-tightening or company restructuring though distressed periods are just as useful for settling old scores and shaping up new partnerships. Testifying to the purifying effects of market downturns, Sudan and South Sudan, countries that share the painful experience of the Second Sudanese Civil War which pitted them one against another, are edging closer to increase cooperation by making the shared hydrocarbon reserves a joint venture instead of two separate ones. Juba and Khartoum have signed a draft agreement on the latter’s involvement in South Sudan’s oil production, providing technical and financial aid to restart Block 5A (part of the Nile Blend crude stream). Seemingly a small step, yet one which might kickstart a further intertwinement of the two states’ energy sectors. Sudan will help its southern neighbor to relaunch production from Block 5A (the oil-prolific block which has set off a vicious war in the early 2000s) and will provide technical assistance on blocks 03 and 07, all of them located on the frontier between the two states. Situated amidst a vast swampy area, Block 5A has started producing in 2006 and temporarily peaked at 54kbpd in 2009 yet its production rates plummeted after the 2011 independence declaration and have been hovering in the past years around 5kbpd. According to analysts’ assessments, Block 5A has a production capacity of 80kbpd (the grade is Nile Blend). Blocks 03 and 07 form the main producing portfolio of South Sudan’s oil industry, with their total output amounting to some 130-140kbpd.

Ever since becoming independent, South Sudan has sought to ramp up crude production to 350kbpd, a level oftentimes described as the nation’s pre-2011 output level. All this despite South Sudan’s close interaction with OPEC+ – Juba has not only participated and committed to the initial 2016 OPEC+ Vienna deal, it has remained an OPEC+ supporter own production targets notwithstanding. Part of Juba’s support for the OPEC+ production cuts lies in its blatant non-compliance. According to the South Sudanese authorities, the nation has produced some 165kbpd in September 2020, ie. not only more than the 106kbpd it committed to as a target but also more than the 140kbpd output it had at the time of joining the OPEC+ production curtailments.

South Sudan’s production throughout 2020 might have been even higher were it not for the fact that the country’s rather outdated wells have an increasing water take. Beyond the need for technological expertise, maintaining a healthy relationship with South Sudan’s northern neighbor and simultaneously the loading place of all of its cargoes is a prerequisite for its oil future. The 250kbpd Greater Nile Oil Pipeline (it is operated by CNPC, therefore devoid of operatorship-related issues) remains the only conduit that can take South Sudan’s production to a seaside port, namely Port Sudan. In the first years following the youngest African nation’s secession there was some talk of building a pipeline to Port Lamu in Kenya or perhaps even to Djibouti yet due to the heavy costs involved (some $5-6 billion) the project quickly went down the drain.

Creating a working Sudan-South Sudan axis remains a key challenge for the sustainable future of East Africa, considering that the latter still pays a 24.1 USD per barrel pipeline transportation tariff for Dar Blend and a 26 USD per barrel tariff for Nile Blend. This might seem an unprecedented transportation rate even for such a conflict-ridden region yet the main element of the tariff consists of South Sudan’s arrears vis-à-vis the northern neighbor – so far Juba has paid out some $2.5 billion out of the $3 billion agreed at the time of secession and presumably will continue to pay until 2022; the same year that the transportation agreement runs out. Against such a complex background full of challenges, it should not come as a major surprise that South Sudan is inclined to join OPEC as a full member.

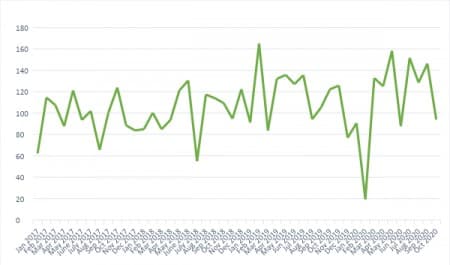

Graph 1. Crude Exports from Sudan in 2017-2020 (thousand barrels per day).

Concurrently, as part of its crude strategy transformation, South Sudan has pledged to quit its heretofore often used practice of getting advance payments in exchange for future cargo allotments. This will be a palpable blow for the usual consumers of South Sudanese crude in China, Malaysia and other countries as pre-financed deals up to now guaranteed a 10-percent discount (in the pre-COVID period this meant that off-takers could get the crude 6-7 USD per baller cheaper than its assumed market value). Yet not everything is lost on the issue – despite South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir signing a directive to end pre-financed deals, discounts will still be offered to companies that provide loans for infrastructure projects.

As South Sudan is trying to settle all its oil-related dilemmas, its overall non-oil economic stature remains dire; in the Doing Business 2020 rating the country ranks as the 185th globally (out of 190 nations) and the COVID-related economic recession is hitting its prospect harder than expected. The oft-mooted 1st South Sudanese Licensing Round was delayed at least one year into the future – back in the days it was assessed to take place in Q1 2020. Concurrently President Salva Kiir has ousted both his Minister of Petroleum and the head of the national oil company Nilepet. Given that some 86-87% of government revenue comes from crude purchase sales and amidst low prices profits in South Sudan’s onshore projects this flow has dried up significantly, urgent and brave decisions are needed.

Không thể sao chép