Back to the news list

Back to the news list

Latin America has a long history of resource nationalism, particularly when it comes to petroleum. Since the end of World War Two, this has acted as a significant deterrent for international energy majors seeking to invest in the region’s vast hydrocarbon potential. This is being amplified by the heightened geopolitical risk and instability that is emerging in Latin America. One country which less than a decade ago garnered headlines for all the wrong reasons after nationalizing its integrated oil company was Argentina. The Latin American country is viewed as a pariah state among financial markets and investors after defaulting nine-times on its foreign debt. The 2012 nationalization of YPF sent shockwaves through the ranks of already nervous offshore energy companies eyeing the vast hydrocarbon potential held by Argentina’s Vaca Muerta shale.

A crumbling economy, dwindling fiscal resources, and overwhelming sovereign debt coupled with hyperinflation as well as a rapidly devaluing currency makes it vital for the central government to tap Argentina’s substantial petroleum wealth. Buenos Aires views the Vaca Muerta, which is often compared to prolific Eagle Ford shale, as a silver bullet for the country’s deep economic woes. While the Vaca Muerta, according to the U.S. EIA, holds 16 billion barrels of technically recoverable shale oil and is the world’s second-largest shale natural gas deposit, it may not be the panacea the central government believes it to be. A key problem is that to fully exploit the Vaca Muerta considerable capital, technology, and knowledge are required which can only come from offshore energy companies. Many continue to view Argentina and its erratic policies with considerable suspicion, especially since the return of a Peronist President.

There are growing fears since the October 2019 general election, where Peronist presidential candidate Alberto Fernández defeated business-friendly incumbent Mauricio Macri, that oil nationalism would remerge in Argentina. That along with the appointment of former president Cristina de Kirchner, the architect of YPF’s 2012 nationalization, as vice president has triggered alarm bells among foreign oil companies and investors.

During 2012, as an energy crisis emerged, de Kirchner chose to nationalize privately owned but one-time Argentine national oil company YPF. The company was privatized in 1993 by then-President Carlos Menem with Spanish integrated energy major Repsol eventually acquiring a 57 percent controlling interest in 1999.

After two decades of being a net energy exporter, a combination of declining petroleum production and growing energy consumption saw Argentina become a net energy importer in 2011. As a result, the crisis-prone Latin American country that year recorded its first energy trade deficit since 1987. That placed considerable pressure on the already fragile economy and further weakened the central government’s already fragile fiscal position. This caused crucial GDP growth to decline, expanding by 4.8 percent during 2011 or nearly half of the 9 percent recorded a year earlier. The economic deterioration coupled with softening petroleum production and steadily rising energy imports, notably natural gas imports from Bolivia, saw de Kirchner choose to renationalize YPF as a solution. In April 2012 Argentina’s congress approved de Kirchner’s bill seeking to seize a 51 percent controlling stake in YPF from Repsol.

The rationale for the decision was simple, Argentina’s government believed that Repsol had failed to provide sufficient capital to YPF so that it could ratchet up exploration and oilfield development activities aimed at boosting Argentina’s oil reserves and energy production. That lack of investment was preventing YPF from exploiting the vast petroleum reserves of the Vaca Muerta formation which Buenos Aires believed would resolve its economic ills.

Now, with an even severer economic crisis materializing, along with a Peronist President Fernandez and his Vice President de Kirchner being in the Pink House, there are very real fears that the nationalization of petroleum assets could prove to be a tempting solution to the current crisis. Those fears are being stoked by a weak economy which before the COVID-19 pandemic was facing its third year of recession in 2020, dwindling energy investment, and weaker than expected energy production.

The risk of a resurgence in oil nationalism in Argentina is further amplified by the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. Some economists are predicting record economic contraction for Argentina, forecasting that GDP will shrink by up to 12 percent during 2020 which is greater than the 11.8 percent contraction recorded during the 2002 economic crisis.

Investment in Argentina’s crucial energy sector is drying up. The March 2020 oil price crash forced oil companies to slash capital expenditures and shutter uneconomic wells. Operations were suspended in response to Buenos Aires’ strict quarantine lockdown aimed at curbing the spread of the coronavirus. Oil output fell sharply to an average of 469,374 barrels per day for July 2020 which was 7 percent lower than the equivalent period in 2019. Natural gas output also declined significantly losing 12 percent year over year to just under 798,000 barrels of oil equivalent.

Argentina Annual Hydrocarbon Production

2020 data is the average for 1 January to 31 July 2020.

That is magnifying the pressure on Argentina’s fragile economy and the central government’s weak finances. The severity of the crisis facing Buenos Aires is underscored by the government defaulting yet again on its sovereign debt in May and having to negotiate terms with foreign creditors. It is difficult to see any sustained production recovery occurring. Oil’s prolonged price slump combined with high breakeven costs for new projects in the Vaca Muerta, which are estimated exceed $50 a barrel or more than $6 greater than the current Brent price, are weighing upon investment. This is not being helped by Argentina’s long history of erratic energy policies, particularly with the architect of the YPF nationalization residing in the Pink House.

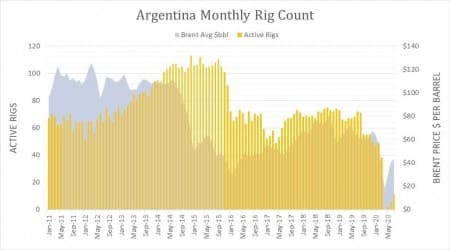

If drilling activity is used as a proxy measure for activity in Argentina’s oil patch, it is worrying to see that the number of operational rigs has fallen sharply since 2015.

Argentina Monthly Rig Count

As you can see even before the COVID-19 pandemic the number of rigs had dropped off sharply to be 49 at the end of February or 26 percent lower than a year earlier and less than half of the 106 operating rigs for that month in 2015.

Even reassurances from President Fernandez, along with his administration implementing a $45 per barrel Brent reference price, it could take years for Argentina’s oil industry to recover. The economic conditions that now exist in Argentina are worse than those which precipitated the nationalization of YPF in 2012. Buenos Aires has done little to allay fears that, as Argentina’s economic crisis worsens, the government will not resort to similar measures to secure oil and natural gas supplies.

Không thể sao chép